Key Takeaways

- CRISPR is a precision tool for gene editing, giving humanity the power to rewrite DNA and cure genetic diseases.

- Jennifer Doudna’s leadership blends innovation with ethics, emphasizing responsible scientific progress.

- The greatest challenge of gene editing is social, not technical – equitable access will determine its global impact.

- Ethical innovation requires foresight – Doudna’s advocacy ensures guardrails evolve with discovery.

- The CRISPR revolution is redefining what it means to create, merging science, morality, and human identity.

The Dawn of a New Biological Era

For centuries, medicine focused on treating symptoms. Then came the genomic age – and with it, the possibility of treating the cause: our DNA itself.

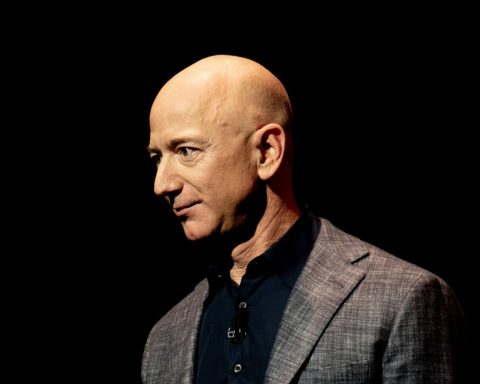

In 2012, biochemist Jennifer Doudna, alongside French scientist Emmanuelle Charpentier, made a breakthrough that would redefine the limits of biology. Their discovery of CRISPR-Cas9, a molecular tool for editing genes with unprecedented precision, marked the beginning of a new scientific epoch.

CRISPR – short for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats – sounds technical, but its essence is simple: it gives scientists the ability to “cut” and “paste” sections of genetic code. It can correct mutations that cause diseases, engineer plants to resist drought, and potentially eliminate inherited disorders.

But the power to rewrite life also introduced profound ethical and social questions. How far should humans go in editing themselves? Where do we draw the line between healing and enhancement?

Few innovators have had to navigate both scientific revolution and moral reckoning at once. For Jennifer Doudna, that paradox became the defining challenge of her career.

A Discovery That Changed Everything

The story of CRISPR begins not in a lab but in nature. Doudna’s early research focused on RNA, the molecular cousin of DNA that carries genetic instructions. She studied how bacteria defend themselves against viruses – a seemingly narrow field that would, unexpectedly, hold the key to rewriting human biology.

What she and Charpentier uncovered was a microbial defense system: when attacked by viruses, bacteria store snippets of viral DNA in their own genome. These snippets – the CRISPR sequences – help bacteria recognize and destroy future invaders using a protein called Cas9, which acts like molecular scissors.

Doudna realized that this bacterial immune system could be re-engineered as a universal gene-editing tool. In her lab at UC Berkeley, she demonstrated that CRISPR-Cas9 could be programmed to target any DNA sequence – not just viral ones – and cut it with surgical accuracy. Scientists could then delete, insert, or modify genes as easily as editing text in a document.

It was a revolutionary idea – one that moved biology from observation to creation. Within a few years, labs worldwide were using CRISPR to engineer crops, model diseases, and explore gene therapies. By 2020, Doudna and Charpentier were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their groundbreaking work.

Yet even as the scientific world celebrated, Doudna was haunted by a question: what if this tool fell into the wrong hands?

The Promise and Peril of Power

The potential of CRISPR is staggering. It could one day cure genetic diseases like sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, and muscular dystrophy. It could make agriculture more resilient, eliminate mosquito-borne illnesses, and even slow aging.

But it also opens the door to “designer genetics” – altering embryos to enhance intelligence, appearance, or physical ability.

In 2015, Doudna experienced a moment that reframed her mission. She dreamed that Adolf Hitler approached her, asking to understand how CRISPR worked. The nightmare jolted her into recognizing the immense moral weight of her discovery.

Since then, she’s become one of the leading voices for ethical guardrails in biotechnology. Through her organization, the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI), she has championed transparent research, equitable access to genetic medicine, and international cooperation to prevent misuse.

This balance between innovation and ethics is what defines her legacy – and offers a model for how future breakthroughs should be led.

Editing the Future Responsibly

The next decade will test whether humanity can wield CRISPR responsibly.

Already, clinical trials using CRISPR are showing promise. In 2023, the U.S. FDA began reviewing gene-editing therapies for rare blood disorders – a milestone that could make curing disease at the DNA level a clinical reality.

Meanwhile, CRISPR-based diagnostics are being developed for rapid disease detection, including viruses like COVID-19. In agriculture, gene-edited crops may help secure global food supply amid climate change.

Yet, the greatest challenge may not be scientific – it’s social. Who gets access to these life-altering technologies? Will genetic innovation deepen inequality or democratize health?

Doudna believes inclusion must be part of innovation. She advocates for “open science” – making CRISPR tools accessible to researchers and nations worldwide, not just private corporations. Her work at IGI supports projects from malaria-resistant mosquitoes in Africa to gene-editing education programs for students.

A New Frontier of Human Agency

Jennifer Doudna’s journey represents a fundamental shift in how we understand leadership in science. She didn’t just invent a tool; she created a framework for rethinking the relationship between discovery, power, and morality.

Her story shows that true innovation is not just about invention – it’s about stewardship.

We now live in a world where humanity holds the pen to its own genetic script. The question Doudna leaves us with is not whether we’ll use that pen, but how we’ll choose to write our story.

In that sense, the CRISPR revolution is not just about editing genes. It’s about editing our collective understanding of responsibility – and what it means to be human.

FAQs

1. What is CRISPR and how does it work?

CRISPR-Cas9 is a gene-editing system derived from bacteria. It uses a guide RNA to locate a specific DNA sequence and the Cas9 protein to cut it, allowing scientists to modify genes with precision.

2. What diseases could CRISPR potentially cure?

Clinical trials are exploring treatments for sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, and certain forms of blindness.

3. Why is Jennifer Doudna’s discovery considered revolutionary?

CRISPR democratized gene editing by making it simpler, cheaper, and more accurate than previous techniques – transforming nearly every field of biology.

4. What are the ethical concerns surrounding CRISPR?

The technology could be misused for non-medical enhancements or unequal access, leading to social and ethical dilemmas around “designer genetics.”

5. What’s next for CRISPR innovation?

Researchers are refining CRISPR for safer human applications, developing new variants like base and prime editing, and exploring its use in agriculture and environmental sustainability.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jennifer_Doudna

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CRISPR

- https://ipscell.com/2015/11/haunting-doudna-nightmare-about-hitler-wanting-crispr/

- https://chemistry.berkeley.edu/news/nobel-laureate-jennifer-doudna-on-crispr-future-gene-editing

Photo credit: Christopher Michel / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 (link)